Russia’s key disinformation narratives addressed to Poles - Fakehunter analysis

In Russia’s ongoing disinformation war, one can already talk of a "dedicated product,” that is propaganda messages based on what appears to be comprehensive analysis - taking into account Polish realities of life, fragments from some of the country’s tragic history, and Polish society’s likes and resentments. The channels used by Russian propagandists aiming to get into the minds of Poles are mainly social platforms, especially Twitter.

Since the start of Russia's attack on Ukraine, an intense propaganda war in cyberspace has been waged, a main target of which has been Poland - one of Ukraine's main allies. Every day, the Polish internet is flooded with information intended to create a false impression of the causes and course of the conflict designed for Polish recipients.1

Analysis of such messages shows that several directions are clearly demarcated, intended to sow fear and doubt in Polish public opinion, foster a sense of danger and discourage people from helping war victims. Reactions to them and their subsequent reproduction indicate that many Polish internet users are often unaware that the sensational reports, rumours and often seemingly unbiased entries they read on social platforms - and then uncritically liked or forwarded - have actually been invented by the Russian propaganda machine and disseminated through explicit or disguised sources associated with it.2

The weapon Russia uses in this fight is disinformation, i.e. manipulated messages created by Kremlin propagandists to build a false image of reality in the minds of Polish recipients.

From the very beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin propaganda has deployed universal narratives, i.e. addressed to international public opinion. Fabricated materials are created to obscure the true picture of the war, to present Russian actions as a peace operation and Russia as the liberator of Ukraine from foreign influence. In addition, there are constant attempts to provoke conflict in societies that are hostile to Russia, as Moscow sees it, as well as systematic undermining of the meaning and values of democratic institutions.

Narrative 1: “Ukrainian refugees are a pest"

Messages addressed to a specific recipient are also created with the obvious goal of Russian propagandists to fuel Polish-Ukrainian conflict.

Since the beginning of the war, the Polish internet has been bombarded with content intended to confuse Poles; opinions about refugees from Ukraine, in line with the basic principle of Russian disinformation, described in the report of the US Department of State in August 2020 entitled ‘The Pillars of Russia's Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem.’3

Such messages create an atmosphere of fear related to the fact that almost 4.5 million refugees have appeared in Poland in a relatively short time. The purpose of such fake news is to spread anxiety about the mass influx of people fleeing the war and is designed to sow fears that Poles’ security and socio-economic situation will worsen.

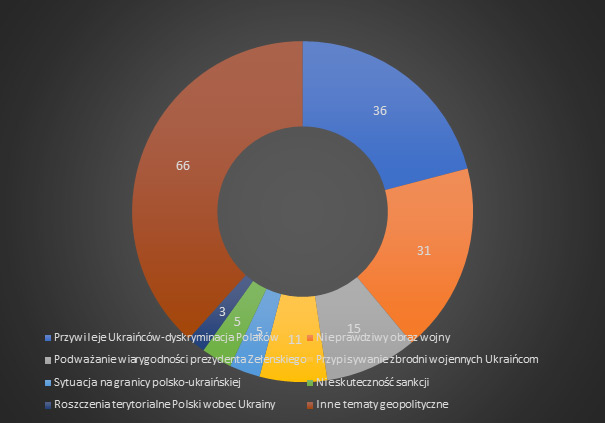

The chart below shows the thematic profile of reports submitted to #FakeHunter since February 24, 2022.

In the first days of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, one post began to circulate on the Polish internet that "Polish children are being thrown out of oncology hospitals to make room for Ukrainian children." The source of these reports was “a neighbor" whose four-year-old son was discharged from hospital. "They were kicked out of the oncology hospital because there was no place for Ukrainian children." After this fake news was rapidly denied by Polish oncologists, the message shifted focus, with entries beginning to talk of the wider alleged priority of treatment for refugees in Polish hospitals and clinics.

The subsequent days of the war brought new variants of this narrative, which was crucial from the point of view of Polish-Ukrainian relations. There were, for example, anonymous stories about the alleged prioritising of Ukrainian students in Polish schools. Other entries pushed the idea that helping Ukrainian refugees was happening at the expense of Poles, with Ukrainians benefitting from preferential access to transport and cultural institutions. Pupils and students were, the messages said, being thrown out of student halls to make room for their neighbours from across the eastern border and that the queues in public offices were the result.

The narrative that Ukrainians would replace Poles on the Polish labour market has been pushed particularly hard on social platforms. The key frame is that Polish employers receive subsidies for employing Ukrainians. The authors of the narrative shifted rapidly from the general to the specific - publications began to appear that did not so much outline the possible threat, but cite "living" examples. Specific companies were named which carry out alleged collective layoffs to be replenished by a workforce made up of Ukrainians.

When the Polish government announced in early April that refugees would be issued a PESEL (social security) number, so they could, inter alia, use digital services, the response of the Russian disinformation apparatus was immediate - the network was flooded with reports that Ukrainians would receive Polish citizenship - and that the purpose of the operation was to win new voters for the ruling party. At the same time, a narrative was created that people who had fled Ukraine before the war were not refugees, but displaced persons.

When the Polish central bank announced at the end of March it would launch a hryvnia-to-zloty currency exchange system, the Kremlin's reaction was immediate. Social platforms were flooded with the outrageous information that the exchange was to be carried out at a 1:1 ratio. Some internet users, without waiting for the actual conversion rate (which is approximately PLN 0.14 per hryvnia), bemoaned that the government and the National Bank of Poland were undertaking harmful monetary policy measures. 4

Old photos and edited videos - sometimes with authentic videos thrown in alongside fake comments - are often used to make fake news credible. For example, a photograph of a board hanging briefly in 2017 in a store in Szczecin about Ukrainians emptying a cash register, have recently also sought to pay testimony to the criminal nature of the refugees. In turn, an article from 2019 about the case of a Polish student who was punished for reminding a Ukrainian colleague about the crimes of the WW2 Ukrainian nationalist group UPA was designed to serve as proof that Poles are currently not allowed to tell children in schools about the Ukrainian genocide in Volhynia. Other profiles also remind readers of the Banderites (after UPA’s leader) daily, and when real information appeared online that just before Easter, in several places in Volhynia, in gratitude to Poles hosting refugees, local Ukrainians had tidied up local Catholic cemeteries, it immediately appeared on Twitter that this had been done by Poles, not Ukrainians.

Russian propaganda conducts so-called ‘probing communication,’ involving the admission of false information online designed to raise emotions, create anger and an aversion towards Ukrainians among specific social groups who may be more susceptible to such reports or feel threatened, e.g. patients, people on social assistance or the unemployed.5

Most of these reports are not based on facts but emotions, and their purpose is to sow dislike or even hatred towards Ukrainians, introduce chaos and deepen internal divisions in Polish society. 6

Narrative 2: "Polish-Ukrainian territorial claims"

Polish-Ukrainian resentments have turned out to be a very useful tool of Russian propaganda aimed to undermine the image of Ukrainians in the eyes of Poles. The Kremlin eagerly and often successfully exploits some of the painful threads in the history of both nations. Greater rapprochement between Poland and Ukraine seems in turn to induce pro-Kremlin propaganda into even stronger messages in this area.

The key false narrative of this type is the message about the alleged partition of Ukraine being prepared by the Polish government. Fake news is not new, but the war in Ukraine has refreshed and intensified this type of narrative. The first mention of the alleged territorial claims that Poland intends to make against Ukraine appeared on the eve of Russia's invasion. At that time, a sensational message from pro-Russian Ukrainian deputies, who claimed that Poland was preparing for the annexation of Western Ukraine, was disseminated online.

The Kremlin is also trying to reverse the vector of alleged territorial claims, with President Zelensky allegedly using Poland's military and economic aid to make secret efforts on the international arena to reinforce its sovereignty over border areas such as Biała Podlaska, Chełm and Przemyśl.

Narrative 3: "Poland has entered the war"

The Kremlin is trying to undermine Poles’ confidence in their own government with reports that Poland is quietly and without the knowledge of Polish society about to join (or has even already joined) the war with the Russian Federation. Sensational information, such as Polish tanks entering the Kaliningrad Oblast, are as unreliable as they are easy to debunk. However, the Russian propaganda apparatus is also producing even heavier arsenal. At the beginning of May, a photo of an order to put three battalions of the 6th Airborne Brigade on alert, which would then allegedly secure facilities in the Lviv and Volyn districts, shifted from Telegram into social networks. Under the order was the signature of the General Commander of the Armed Forces, General Jarosław Mika. Although the Ministry of National Defense widely denied the veracity of the document, the order of the Chief of the General Staff of the Polish Army, Gen. Rajmund Andrzejczak regarding vaccination against Covid-19, remains online .7

Narrative 4: "They want to make us forget about the massacre in Volhynia"

One of the specific pro-Russian narratives addressed only or mainly to Poles is the theme of the WWII massacre in Volhynia. The genocide committed over 80 years ago on the Polish population in the borderlands by Ukrainian nationalists is a key topic for Russian propaganda, fitting perfectly with the Kremlin's message that Russia is liberating Ukraine from Nazis.

Experts from the East StratCom Task Force, which is currently working on the topics of disinformation in international cyberspace wrote in their analysis of April 12, 2022: "The Massacre in Bucza: How to distract attention in Poland,”8 drew attention to a new and interesting application of the narrative about the Volhynian massacre. In their opinion, this thread was on the list of top trends on Polish Twitter on April 4 and 5. The date is not accidental, coming only a few days after the Russians withdrew from Bucza, the entry of Ukrainian troops into the town and the disclosure of the crimes committed by the Russians who had been there after February 27.

Pro-Kremlin narratives circulating in the Polish information community have highlighted several threads: that the events in Bucza are not a true genocide, because the Volhynia massacre was many times greater; that Poles should remember about unresolved historical Ukrainian crimes; that Ukrainians and others responsible for anti-Polish actions should now they face the consequences of their actions. The alleged parallel between Bucha and Volhynia is the key point.

In this situation, it is invaluable to make Polish internet users and social platform users aware that by uncritically duplicating such narratives they are unwittingly becoming a tool in the hands of Russian propagandists. Such a reaction at the social level has been observed often recently.

- 1 https://www.gov.pl/web/sluzby-specjalne/klamstwa-rosyjskiej-propagandy2

- 2 https://cyberdefence24.pl/cyberbezpieczenstwo/rosyjska-wojna-dezinformacyjna-ekspert-celem-rosjan-jest-stymulowanie-paniki-w-polsce-wywiad

- 3 https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Pillars-of-Russia%E2%80%99s-Disinformation-and-Propaganda-Ecosystem_08-04-20.pdf

- 4 https://pieniadze.rp.pl/konta-bankowe/art35948741-hrywny-do-wymiany-ruszyla-akcja-pomocy-banku-centralnego

- 5 https://www.rp.pl/konflikty-zbrojne/art35822351-kamil-basaj-trwa-operacja-rosji-przeciw-uciekinierom

- 6 https://twitter.com/StZaryn/status/1524332174270517251?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1524332174270517251%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fpolskieradio24.pl%2F5%2F1222%2FArtykul%2F2956378Kreml-probuje-fake-newsami-uderza

- 7 https://konkret24.tvn24.pl/polska,108/wojsko-polskie-postawione-do-stanu-pelnej-gotowosci-bojowej-by-chronic-lwow-i-wolyn-ten-rozkaz-jest-falszywka,1104470.html

- 8 https://euvsdisinfo.eu/the-bucha-massacre-how-to-deflect-attention-in-poland